The tale of Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang

17 December 2011

Kate Grimond

On 31 May 1961 Ian Fleming wrote to Michael Howard at Jonathan Cape, publisher of his James Bond novels: ‘I am now sending you the first two “volumes” of Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang. Heaven knows what your children’s book readers will think of them.’ He ended his letter: ‘I am gradually reactivating myself and I hope to be up in London for about two days each week. Though much will depend on a gigantic medical conference this afternoon.’

Six weeks earlier, Fleming had suffered a serious heart attack. He was 52. Despatched to convalesce at a seaside hotel on the south coast and forbidden a typewriter to prevent him from working, he passed the time writing out in longhand the story for his eight-year-old son, Caspar.

Michael Howard replied: ‘Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang’s adventures have me enthralled. She is truly an invention of genius, and I trust you can reel off at least ten more episodes with no trouble at all.’ The professional readers also gave it the thumbs up. ‘Absolutely gorgeous. This is really alive and splendid … BUT BUT BUT... and again but, it is terribly sloppily written.’ Michael Howard asked Fleming: ‘Do you want us to put the editorial sandpaper over it?’ He concluded: ‘All in all ... the concert of opinion is that you have struck gold again.’

Fleming delivered book three later that year. (The book was first published in three volumes and later combined into one). The readers thought it less good than the first two, commenting in particular on the lack of a cliffhanger at the end. Fleming wrote back: ‘I will take note of your advice on the third adventure and get that off to you as soon as possible. But God knows when I am going to get round to a fourth!’ Perhaps he knew that he never would.

The main concept in the book of a magical car with the power to fly and to swim, and a desire to protect its family passengers and assist them in thwarting evil-doing, was a simple and attractive one, and enthusiasm for the book continued throughout 1961. The hitch lay with finding the right illustrator and this took a full two years.

The first choices, newspaper cartoonists, Trog and Haro Hodson, came unstuck for different reasons. Fleming grew disillusioned: ‘I am now absolutely fed up with this whole series and have completely lost the mood.’ He was nonetheless fussed about the depiction of the actual car and asked his old friend Amherst Villiers, to come up with a drawing, reassuring Michael Howard: ‘He is a motor-car and guided-missile designer of absolutely top calibre, and in fact designed the crankshaft of Graham Hill’s BRM which has been winning lately’. Bond aficionados will know that James Bond’s first and deeply loved car was the 4½ litre Bentley with the Amherst Villiers supercharger.

When, finally, the young John Burningham was commissioned in late 1963, Fleming was enthusiastic. He had a few comments on the completed drawings: ‘SHELL on petrol pump instead of ESSO. Exhaust fumes (powerful) to come from exhaust pipes wherever possible. All bottles to have sweets in in Monsieur Bonbon’s shop’. But when asked if he would like to see the galley proofs, he declined.

The truth was that he had never fully recovered from his heart attack. While his fame was increasing by the day with the release of Albert ‘Cubby’ Broccoli’s first Bond films, (Dr No in 1962 and From Russia with Love in 1963), his health was deteriorating. He did little to help himself, continuing to smoke and to drink, and though he was only in his early fifties photographs from the time show a sick man looking much older.

Eventually, on 12 August 1964, Jarrolds, the printers, despatched the first advance copies of Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang, the Magical Car; Caspar Fleming turned 12; and Ian Fleming died in hospital in Canterbury, having been taken ill at the Royal St George’s Golf Club the previous day. He never saw the finished book.

Four years later, Cubby Broccoli produced the film, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, starring Dick van Dyke. Among the cast were Desmond Llewelyn (the long-serving Q in the Bond films) and Gert Frobe (Goldfinger). Though the film was based on Fleming’s creation, Roald Dahl wrote the screenplay and added new elements: the child-catcher for instance and Truly Scrumptious. Sir Ken Adam produced a superb design of the flying car.

One of the reviews of the book had noted the skilful blending of fact and fiction. Fleming would always superimpose his creative imagination on to true events and real objects. There is more of the Bond oeuvre rooted in reality than is generally realised. And so it was with Chitty. He dedicated the book to a real car: ‘To the memory of the original Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang, built in 1920 by Count Zborowksi on his estate near Canterbury.’

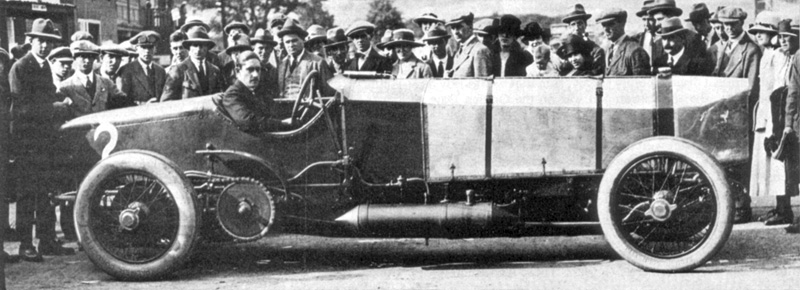

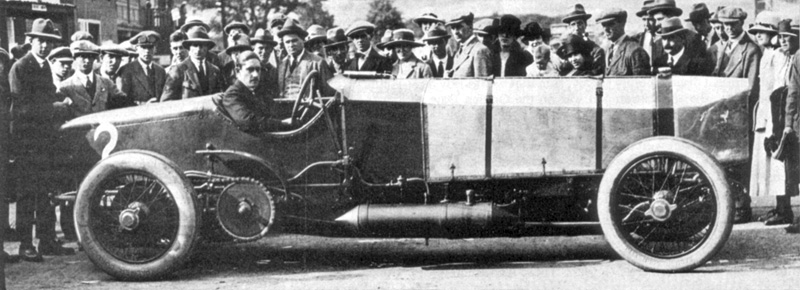

In fact there were three Chitty-Bang-Bangs, (note — one Chitty in the name originally) built and raced by young Louis Zborowski between 1920 and 1924. Louis was the only son of Count Elliott Zborowski and his wife Margaret, a granddaughter of William Backhouse Astor Sr, one of the richest men in America. The Count, whose title was spurious, seems to have been as prosperous as his wife, with property in Manhattan and the Bronx. He was a passionate pioneer of motor racing and was killed racing in 1903. In 1911 his widow, Margaret, bought Higham Park, a vast 18th-century house outside Canterbury, but no sooner had she done so than she died, leaving her son, Louis, who had just turned 16, the house and a staggering fortune.

Louis, after a patchy education, devoted himself to motor racing, as his father had done. Described as having an effervescent temperament, he cuts a dashing figure in old photographs in his elegant suits or black work jacket and jazzy cap. He spent lavishly on motor racing, putting money into Aston Martin at a critical time for the firm, but mainly on building the Chittys at Higham Park, their body-work being made by Bligh Brothers, coachbuilders of Canterbury. Usually described as a monster or leviathan, Chitty 1, the dedicatee, was a massive, five-ton, grey, gleaming, noisy car, with a pre-1914 war, chain-drive, 75 horsepower Mercedes chassis in which was installed a six-cylinder 300 horsepower Maybach aeroplane engine and which had a top speed of 135 mph and almost no braking power.

It was the ease of obtaining government surplus aero engines for between £30 and £60 from the Disposal Board after the first world war that had led to the construction of these magnificent and popular cars. Their appearance at Brooklands was always a notable event and drew enthusiastic crowds. But in 1924, Louis, like his father, was killed at the wheel. He was driving for Mercedes in a car designed by Dr Porsche in the Italian Grand Prix at Monza. Such was his popularity that a statue of Count Louis Zborowski was erected at Le Mans.

Ian Fleming as a young man used to visit Higham Park, a guest of its next owner, Walter Whigham, a partner of his grandfather, Robert Fleming, in the merchant bank of the same name. There he must have heard all about the glorious Chittys, seen exactly where they were built, and heard the stories of the flamboyant Louis.

He rounded off his dedication: ‘In 1921 she won the Hundred MPH Short Handicap at Brooklands at 101 miles per hour, and in 1922, again at Brooklands, the Lightning Short Handicap. But in that year she was involved in an accident and never raced again.’ He added as a postscript: ‘This is a polite way of putting it. In fact Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang suddenly went mad with rage about something, and with the Count at the wheel got out of control and charged through the timing-hut, very fast, backwards!’ The timing-hut was indeed demolished in what was described at the time as ‘the deuce of a crash’.

Now, nearly a century later, Frank Cottrell Boyce has refound Zborowski’s machine, reassembled her, and sent her off on new fictional adventures in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang Flies Again (Macmillan, £10.99).

A curious literary postscript lies in the fact that Chitty 1 was bought by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s sons. After publication Adrian Conan Doyle pointed out a couple of inaccuracies in Fleming’s dedication and it was amended in subsequent editions. He said that the first time he drove Chitty was one of the most exhilarating times of his life, and that he was never able to start the car without a team of at least 11 men.

A retrospective exhibition of John Burningham, including his illustrations for Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang is on show at The Fleming Collection, 13 Berkeley Street, London W1J 8DU until 22 December.

"The Tale of Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang"

Started by

Revelator

, Dec 17 2011 12:29 AM

1 reply to this topic

#1

Posted 17 December 2011 - 12:29 AM

I recently came across this fine article in Spectator:

#2

Posted 17 December 2011 - 12:52 PM

What a most intriguing story, I never knew! Many thanks for sharing this, Revelator!

Here's a picture of Count Zborowski in his leviatan:

Here's a picture of Count Zborowski in his leviatan: